November 2005

"As with any printed music, many interpretations are possible and so it is in the case of the Ursonate."

Kurt Schwitters

As part of their "dadatour" in 1921, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Hoech and Kurt Schwitters visited Prague. On the sixth of September, Raoul Hausmann performed his phonetic poem called fmbsw, composed solely of rhythmically recited letters and onomatopoeic syllables in front of allegedly thousands of listeners. We don’t know anything about the reaction of the Prague audience (a year before that it, such an audience had become so enraged during an avant-garde production by Hausman and Huelsenbeck that the Dadaists had to appease them with several dance numbers). Nevertheless, Kurt Schwitters was completely overwhelmed by the impression he received from the Prague recital of the phonetic poem. It was so inspiring to him that he began to compose a similar poem himself. It was named the Ursonate, or sonata from prehistoric times. Schwitters spent years working on the Ursonate. The first version was written sometime around 1923. Although it is now mostly known as a literary work, the poem resembles a musical composition rather than literature; it even has the structure of a classical music sonata of four movements. For Schwitters, its written record wasn’t as important as its live production. He enthusiastically recited it on many occasions, and in the mid-1920s he recorded it to be released as a record. To perform the whole Ursonata would supposedly take not less than forty minutes, and the full energy of the reciter. The written record was created in 1932 with the help of the typographer Jan Tschichold, and published in the final issue of Schwitters’s magazine Merz. Schwitters’s Ursonate is composed of meaningless rhythmical and onomatopoeic words, and it lies somewhere between nuclear linguistics and parody on literature. Kurt Schwitters broke the words into individual atoms of sound and revealed the construction materials of human communication - but all this for the price of its total destruction. He dismantled the machines of speech into individual wheels that we can inspect in detail and admire, but at the same time, we are unable to put them back together.

In Paris at the end of the 1940s, phonetic poetry was also explored by the Lettrists who even derived the name of their group from it. Expressions on the verge of music, visual art and literature were considered the highest stage of development of art, in what the Lettrists considered to be its most elementary and irreducible form. The Dadaists, with their more than 25-year-old experiments which resembled the Lettrists' like two peas in a pod, were rudely and quite illogically accused of plagiarism by the Lettrists. The old group from Cabaret Voltaire and Berlin, though, did not tolerate this. There is reputedly a recording from 1946 where Raoul Hausmann and the group of Lettrists analysed the question of primacy on the field of phonetic poetry using solely imaginary languages composed of individual letters and syllables. In 1968, the seventy year old Dadasopher feelingly roared into a tin speaking tube, "OFFEAHBDCBDQ!" to justify his primacy. Then he smashed the funnel on the floor and said: "I hope you don’t think that I remember the bullshit from 1918 by heart?"

Ryška’s Ursonate is definitely not an attempt to win laurels in the fields of phonetic or visual poetry, nor does it compete with the Dadaists, Futurists or Lettrists in the traditional modernist discipline of Ideas with Liberated Letters. It could also be said that it has nothing in common with Schwitters’s Ursonate. Ryška doesn’t discover the already discovered, but manages to find what the pioneers of the avant-garde brought back from their journeys to foreign lands. But what are all these formal inventions for, and what do they mean? How do we deal with them?

Outside of the modern era, Pavel Ryška’s Ursonate opens with a screening of old and scratched film materials. It doesn’t matter that this effect is overtly a digital simulation; we cannot find a better gateway into the mythology of modernity. Nevertheless, Ryška views the mythology of modern art through his own personal mythology. There is no Apollinaire, Marinetti or Schwitters at the beginning of his story, only a letter soup that does not really appeal to the narrator’s subject in the form of a black square. A black square, Malevič’s Absolute, but at the same time also a small boy being forced to swallow pea soup, although he is principally bored, and of all things longs for food for thought. He levitates above the salt waters and vaguely understands that the thick proteins in the shape of the letters in front of him are really embryos of words and thoughts. The soup represents a microcosm of possible relationships, a dictionary, the embryonic ocean of life, the Ursonate which means everything and nothing at the same time. Ryška’s square undergoes a metamorphosis, the revelation of potential spaces in the soup floods him with happiness and transforms him into a white square, the attempt for the Absolute even more total than the Absolute which preceded it. And as a still immature God he starts to spell the first syllables of the laws of his new world. The potential artist in a school age, though, is put through tests, exposed to derision and doubts from his surroundings. "What is art good for?" asks the tempter, knowing very well that he will not get a satisfactory answer. Only if the small God perseveres and does not stop spelling out, can he expect the desired entry into the geometrically pure world of art.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, each artistic effort is perforce conceptual, commenting upon the history of its discipline. Artists, Pavel Ryška among them, rake over the history of 20th century art and try to find their perspective from the rubbish heap of movements and styles. During this mournful work, Ryška is assisted by his sense of humour. The history of art in his interpretation becomes an educational farce with a witty point, or a humorous comedy for the informed. The letter soup is not the first case when Ryška discovered avant-garde art in the simplest of things. If we know the history of modernism, the world around us transforms into a fascinating exposition full of thus-far unrecognised readymades.

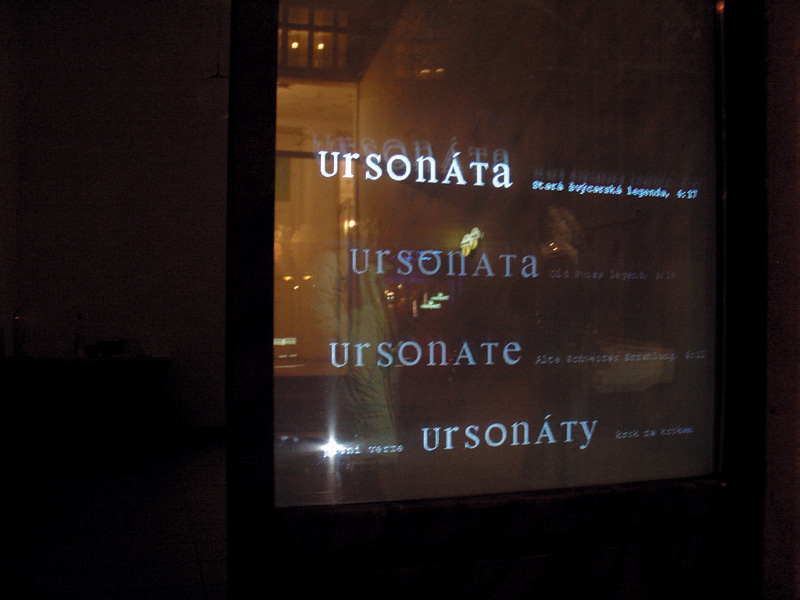

Years ago, Ryška painted large abstract paintings inspired by tourist information signs, minute reminders of radical abstraction in a forest. In his cycle Ideas of Modern Painters, he brought this principle to perfection. The iconic works of artists of the twentieth century become actors in his animated anecdotes. Ryška’s Ursonate is not a lament over the lost originality of the avant-garde, or a melaqncholic post-modern look into the repositories of museums of modern art. Pavel Ryška brings the know-how of modern art out of the museum, and doesn’t hesitate to use it in a comic story which is at the same time a personal confession and an intimate insight into an artist as a young man. The secret of the letter soup can only be understood retrospectively, as the code to it lies in the history of art. That is why Ryška’s Ursonate is a commentary-memory of the newly-understood time of one’s own past. The way in which we are given later interpretations of distant memories is supported by different layers of narration. Apart from the comic bubbles and typographically liberated exclamations, the story also comes with subtitles. Ryška professes to their authorship in such a way that it seems that his role is only to translate and comment upon an already existing legend, from the olden days in the neutral territory of Switzerland. Every work of art, every work of literature begins somewhere with a letter soup, a tractable heap of potato mash, under the table or behind a closet, where at the very beginning of our lives we make many unforgettable discoveries that we try to name in vain until the end of our days. Ryška’s Ursonate has a surprisingly personal and simultaneously joyful climax. The graining of letters and number codes is the very beginning, the ursonate which only then gives rise to the optimistic song of future art.

Tomáš Pospiszyl, 2004

© 2007, etc. galerie

Kateřinská 20, Praha 2, Czech Republic / info@etcgalerie.cz