Can a gritty residue of counter-archives be found in soils, rocks, mounds, as the discourses of materiality organize its forgetting? Does history cling to the world in its erasure, the earth as a collector of disobedience, rebellion, and revolt, claiming time outside the colonial clock?

Kathryn Yusoff1

Imagining the human since the rise of capitalism entangles us with ideas of progress and with the spread the rise of techniques of alienation that turn both humans and other beings into resources.

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing2

In the air, earth, and water, in the cultures of the indigenous people of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, in the pagan beliefs of Europe, and in the contemporary theoretical discourse of new materialism and posthumanism, lives the idea that humans and all other natural entities are interconnected. Our bodies share elements, bacteria and viruses. We draw our energy from the food that grows and matures under the same sun and comes from the same soil we walk on. The inhale of one is the exhale of the other. Along with human and more-than-human material bodies, our stories and destinies are intertwined. The landscape and its inhabitants not only bear human footsteps, but also preserve them. Traces and narratives thus transcend the time horizon of our lives and resonate in the bodies of non-human fellows. Even when it seems that there is no one left to tell or listen to, you should look around and search – complete silence has never existed.

The final chapter of the Beyond Belief series uncovers forgotten narratives that at first glance may seem unbelievable or fictional. But their traces are imprinted in the landscape where they took place, which becomes a unique testimony and an ever-growing archive. In the selected art films, mountains serve not only as specific settings that, by their very nature, shape the course of events, but also as unique figures within historical narratives. The selected videos, each in its own speculative way, expand on the figure of the mountain to address themes of colonialism, extractivism, and the possibilities of resistance to these political forces. Another unifying layer of the curatorial programme is the cinematic reflection on human labour – both as a form of oppressive mechanical dictatorship and as a source of revolutionary potential.

Shadi Harouni is an Iranian-Kurdish artist originally from Hamadan. She currently lives in New York, where she works as an Assistant Professor and Head of the Department of Photography and Video at NYU. In addition to photography and video, her artistic practice also focuses on sculpture and text, archival materials and site-specific interventions. In her recent lecture at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she said that “history is not only marked by official events that are recorded, but by declarations of hope; declarations of the promise of new worlds, peace, freedom, utopia and revolution. (…) And even when that promise is broken, which it often is, it’s not a loss that we, that everything around us, is somehow imbued with that promise. (…) My work as an artist has been to search for images, places, objects… for sentient subjects – humans, animals and plants – that are imbued with the promise of resistance and revolution.“3

Her 2017 film I Dream the Mountain Is Still Whole is set in a black pumice quarry near the town of Bijar in Iranian Kurdistan. The author traces the story of a former Marxist revolutionary and activist who, instead of pursuing teaching and intellectual work, laboured in the stone quarries. Here, in close proximity to the mountain, he and other intellectuals experienced first-hand both the class struggle and the conflict between humans and the landscape. In Harouni’s imaginative interpretation, the life story of an aging dissident, full of physical and ideological resistance, is seeping through the layers of the mountain that has itself been tried and broken away (not only by our protagonist). It becomes a mineral archive, but also a monument to revolutionary dreams and political oppression.

In her work, Mexican artist and researcher Naomi Rincón-Gallardo engages with political satire and mythic narratives through decolonial cuir4 critique and site-specific research. Her films and performances awaken speculative, fictional beings that come from Mesoamerican culture and cosmology, and place them in the context of contemporary neocolonial crises of man and landscape. She says of her practice that it “embraces planetarity, the profound interconnectedness and interdependence between living creatures, minerals, and technical entities, where relationships precede individuality. Death becomes an ongoing, unfinished process, where the dead are integral to collective existence. Life is understood as an immeasurable, unpredictable and relational flux. Affectivity serves as a lubricant, a wet substance facilitating the flow of energy, emotion, thoughts, and materials.”5

In the 2018 film Sangre Pesada (Heavy Blood), the audience is transported to a mountainous landscape scarred by surface mining in the Vetagrande region of Zacatecas, Mexico. The work can be understood as a fictional documentary that explores the resistance of the local population against colonial and capitalist influence. Rincón-Gallardo works with emotions, music, and metaphor rather than factual narration. Yet this is not merely an artistic gesture, but a political act in which non-human and non-European characters take part in the story. The lungs of sex and mine workers are filled with mineral particles, mechanical labor, and a suffocated pleasure carried through telephone wires. An extinct hummingbird searches for sweet floral nectar among the crushed stones. A resistance group made up of insatiable Mesoamerican creatures resembling a vagina dentata is led by a woman with copper teeth, inspired by the destructive Nahua goddess Tlantepuzilama. Together they inhale (and exhale) a toxic political practice full of inequality and rejection, yet they long, they scream for life, for loud passion, revenge, and ecstasy.

In Tellurian Drama, a fictional documentary from 2021 by Indonesian artist and PhD student at Hong Kong City University Riar Rizaldi, the line between fact and imagination dissolves, leaving it uncertain what really happened, what could have happened, or what should have happened. In the video, the author elaborates on his long-term research on the relations between capitalism, technology, extractivism, theory and science fiction.

The film depicts a mountain range near the artist’s hometown of Bandung, where the Radio Malabar radio station was based between 1923 and 1942. This was during the period when the territory of present-day Indonesia was called the Dutch East Indies.6 In 2020, the local Indonesian government decided that the site should become a historical tourist attraction. Tellurian Drama depicts the period between these two historic milestones. It stretches elastically across the 20th century, maintaining the indigenous heritage of his ancestors, in which time is perceived as a flexible actor. This is expressed in the term jam karet (loosely translated as “rubber time”), which itself defies the capitalist understanding of linear, ever-advancing time.

In the artist’s conception, the mountain takes a unique and active role, becoming the central figure of the film, which, alongside the radio signal, captures the tension between coloniality, modernity, and nature. The term tellurian is used as a noun to refer to earthlings, while as an adjective it expresses a relationship to the earth, i.e., anything earthly or relating to Earth. “By including tellurian and drama in the title, I wanted to achieve a film that would not be from my point of view, as a filmmaker, but rather shot from the perspective of a mountain, an expression of the mountain’s thoughts. (…) In Tellurian Drama I worked with my friend, Iman Jimbot, a Sundanese musician who’s engaged in many indigenous practices. His performance enabled the tellurian element – his performance imitates the voice of the mountain.“7

Sara Märc

- Kathryn Yusoff, Inhuman Memory, lecture at the Environmental Humanities Center Amsterdam, 24 May 2023, https://www.materialculture.nl/en/events/inhuman-memory-kathryn-yusoff.

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 19.

- Available on YouTube as part of the Low Residency MFA Visiting Artists & Scholars Series – Shadi Harouni, 2023, School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC).

- The word cuir represents in the Spanish linguistic context, especially within Latin American theory and activism, a linguistic alternative that aims to recontextualize the notion of queer. It offers a decolonial perspective by creating a new term that moves away from Anglo-American queer, focuses on non-normative identities in Latin America, and challenges colonial power structures in language and thought.

- KADIST, In Conversation with Naomi Rincón-Gallardo, accessed 8 September 2025, https://kadist.org/program/in-conversation-with-naomi-rincon-gallardo/.

- This territory remained under Dutch rule from 1816 to 1945.

- FIPRESCI, The Untold History of Indonesia, accessed 8 September 2025, https://fipresci.org/talent-press/the-untold-history-of-indonesia/.

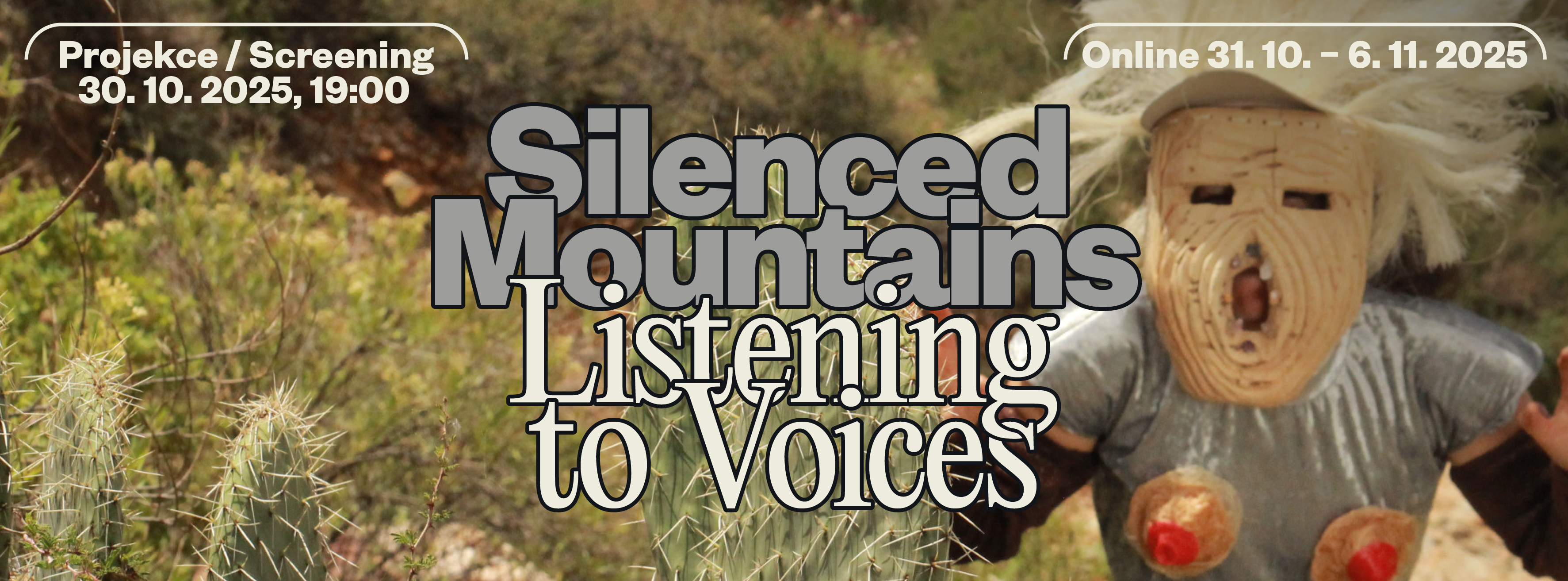

Screening: 30. 10. 2025, 19:00 (etc. galerie, Sarajevská 16, Prague 2)

Online screening on etc. gallery web: 31. 10. – 6. 11. 2025

Curator: Sára Märc

Graphic design: Nela Klímová

Production: Tereza Vinklárková, Nela Klajbanová

Curatorial text translation: Jak Ciosk

Czech proofreading: Michal Jurza

Timing and translation of subtitles: Markéta Effenbergerová

Web support: Ondřej Roztočil

The project is supported by the City of Prague, Prague 2 District, and the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic.